Imagine sitting alone in silent utter darkness, trying to make sense of the world when the only clues you receive are bursts of electrical and chemical signals. Was that latest burst a good message or a dangerous one? You fire back a response, and evaluate the results. Did that make you safer? Happier? Or did that make things worse? Slowly, bit by bit, you tease out which signals mean what, and which responses give you desirable results.

Imagine sitting alone in silent utter darkness, trying to make sense of the world when the only clues you receive are bursts of electrical and chemical signals. Was that latest burst a good message or a dangerous one? You fire back a response, and evaluate the results. Did that make you safer? Happier? Or did that make things worse? Slowly, bit by bit, you tease out which signals mean what, and which responses give you desirable results.

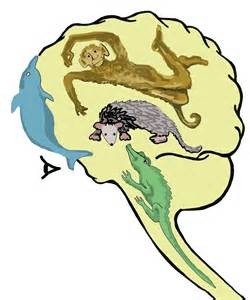

That, in a nutshell, is what happens in the baby brain—actually, in all brains. This formidable-yet-fragile organ is cloistered in the cranium for its own protection, unable to have direct contact with the world.

(Just imagine being a blob of tofu on the loose, and suddenly, being locked up snugly in a skull doesn’t sound so bad.) Everything your brain knows about life it learned from the stimuli intercepted by the rest of the body and routed up through various neural pathways.

(Just imagine being a blob of tofu on the loose, and suddenly, being locked up snugly in a skull doesn’t sound so bad.) Everything your brain knows about life it learned from the stimuli intercepted by the rest of the body and routed up through various neural pathways.

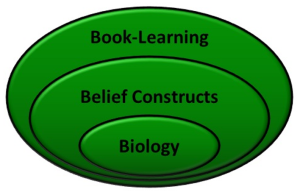

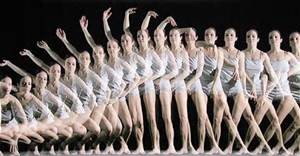

Your brain’s earliest responses to those stimuli are initially programmed by basic biology (genetics), and are pretty quickly shaped by the environment, as well (epigenetics)—even in utero. Because infants are non-verbal, there’s no point in asking them directly to report on their emotional state or describe how they are feeling. At this stage, the baby brain’s repertoire of responses is limited to physical actions; it can tell the arms to wave, or the eyes and voice to cry. It can direct the eyes to look at a particular spot, and hold attention for a short time or a longer time.

Scientists have learned to track and measure these outward behaviors as visible signs of what’s going on inside the depths of the brain. Psychologist and researcher Dr. Jerome Kagan stands at the forefront of investigation into the biological roots of  personality, and is considered one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century.

personality, and is considered one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century.

Kagan has spent decades exploring the nature and source of individual temperament. The Oxford Dictionary defines temperament as “a person’s or animal’s nature, especially as it permanently affects their behavior.” Similarly, Merriam-Webster explains it as “characteristic or habitual inclination or mode of emotional response.”

In his book, The Temperamental Thread (2010), Kagan explains that he and numerous other researchers are working to determine how babies’ brain anatomy and biological conditions shape their life-long emotional responses, self-development, and approach to life. To do this, they began by observing, categorizing, and labeling infants’ physical behavior in response to various stimuli.

Imagine a researcher coming at Baby You with a piece of ice. When that nasty cold cube comes into contact with your chubby cheek, you will typically have one of the following four reactions to this minor discomfort:

Imagine a researcher coming at Baby You with a piece of ice. When that nasty cold cube comes into contact with your chubby cheek, you will typically have one of the following four reactions to this minor discomfort:

- Cry lustily, and keep on crying even when cuddled

- Cry lustily, but calm down quickly with a little cuddling

- Cry softly, and keep on crying even when cuddled

- Cry softly, but calm down quickly with a little cuddling

In addition to the above four types of response to discomfort, Kagan found another four patterns in infant reactions to stimuli that are startling, but not actually painful or frustrating (aka novel events). Baby You would do one of the following, upon seeing

assorted unfamiliar objects being gently waggled before your eyes:

- Move energetically and cry frequently—called the high-reactive response

- Move energetically and cry rarely

- Stay still and cry frequently

- Stay still and cry rarely—called the low-reactive response

Still other patterns of behavior are revealed by responses to frustration, and by spontaneous babbling, smiling, and waving when there are no visible stimuli. Kagan posits that infants probably have somewhere between 15 and 23 fundamental patterns that form the basis for temperament.

So far, this all sounds like Basic Research 101: make observations and categorize results. Ho-hum. But here’s where Kagan’s work gets really sexy!

He hypothesized that he could look at an individual infant’s response to a novel event and make accurate predictions about the personality of that individual as an adult.

Let’s say that Baby You consistently exhibited a high-reactive  response to a novel event. Whenever an investigator gently moved a new stuffed animal above your crib or gave you a whiff of rubbing alcohol on a swab, you wriggled around vigorously and howled loudly to express your feelings about these unfamiliar experiences. Based on these observations, Kagan could predict with statistically significant reliability whether the Adult You would be an introvert or an extrovert.

response to a novel event. Whenever an investigator gently moved a new stuffed animal above your crib or gave you a whiff of rubbing alcohol on a swab, you wriggled around vigorously and howled loudly to express your feelings about these unfamiliar experiences. Based on these observations, Kagan could predict with statistically significant reliability whether the Adult You would be an introvert or an extrovert.

Place your bets—which result would you imagine to be true: High-Reactive = Extrovert —OR— High-Reactive = Introvert?

For now, I will leave Adult You in suspense. But be patient. All will be revealed in the next post!

~~~

stem. Right or wrong, your belief constructs are your own.

stem. Right or wrong, your belief constructs are your own.

from parentheses), the

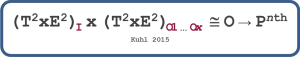

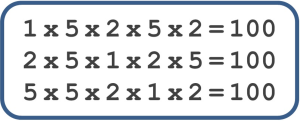

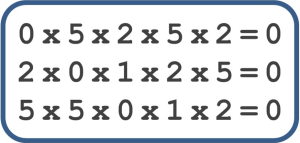

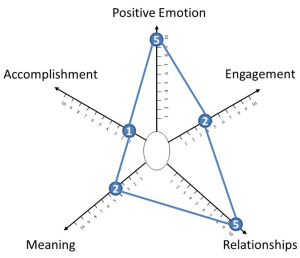

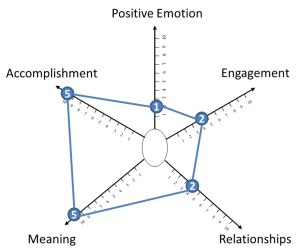

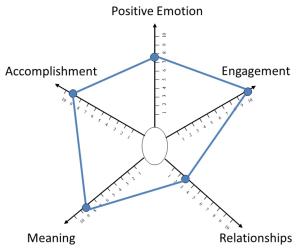

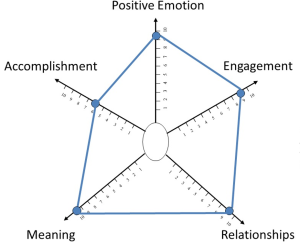

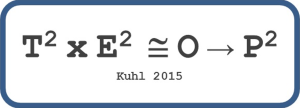

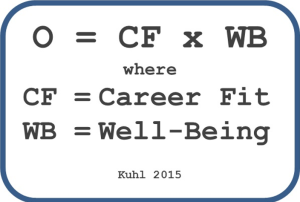

from parentheses), the  , Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment, which I’ve notated as a multiplication equation. (Don’t blame Dr. Seligman—the equation notation is my own elaboration.)

, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment, which I’ve notated as a multiplication equation. (Don’t blame Dr. Seligman—the equation notation is my own elaboration.)

ment company in the world.

ment company in the world.